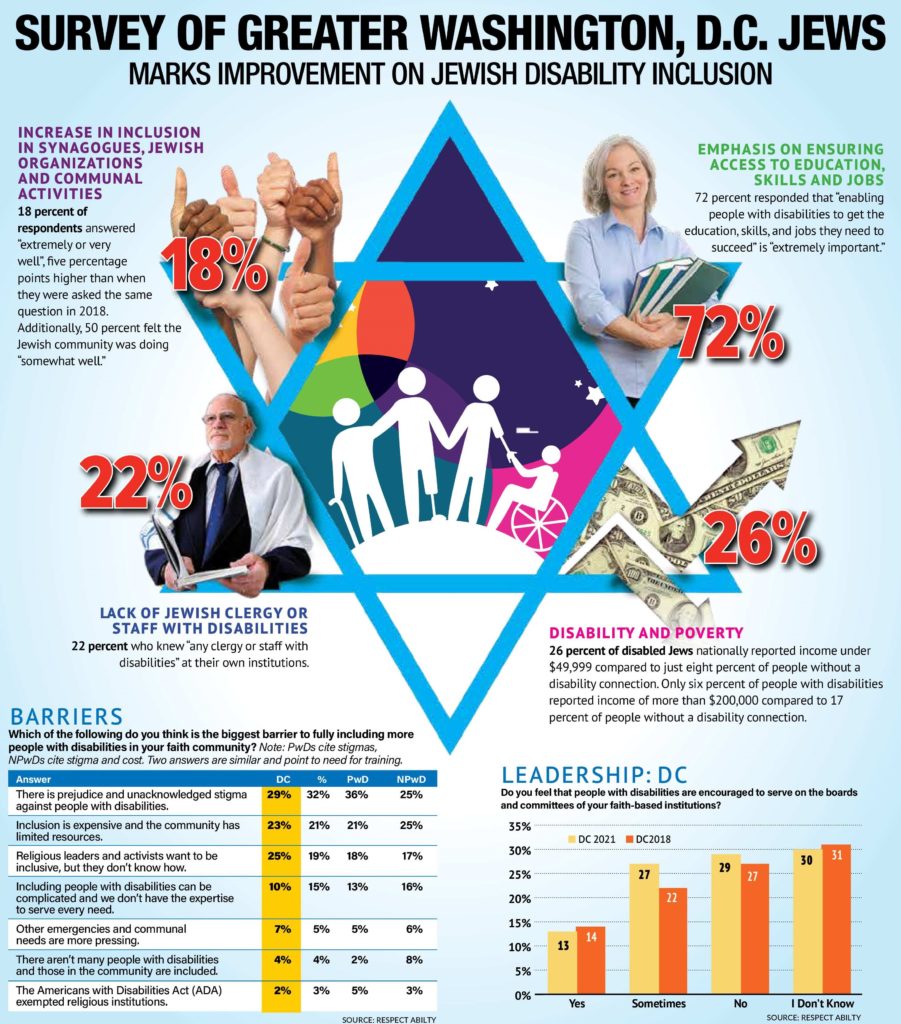

A recent national poll found that 68 percent of Washington-area Jews feel the Jewish community is “better” at disability inclusion compared to five years ago. There’s still room for improvement in including people with disabilities among the ranks of rabbis and the staff of Jewish organizations. And community members can work harder to battle their prejudices against disabled people. The survey, released to coincide with Jewish Disability, Awareness and Inclusion Month in February, highlights the importance of valuing the opinions of disabled Jews.

“I think it’s really important to celebrate the progress we have made without losing perspective that there is still work to do,” said Rabbi Lauren Tuchman, a Maryland spiritual leader and educator, and the first blind person to be ordained as a rabbi.

The survey was conducted nationally by RespectAbility, a disability-led nonprofit in Rockville, then broken down to show local results. Between Oct. 5 and 19, 2021, RespectAbility asked 2,924 Jews, 172 of them from the Washington area, questions about their experiences with disability inclusion in various Jewish institutions. They distributed the survey through email blasts and individual outreach to Jewish leaders. The survey was not a random sample.

Vivian Bass, RespectAbility’s vice chair overseeing its Jewish inclusion work, said, “The survey findings were very encouraging, demonstrating the Jewish community is headed in the right direction. It’s important to celebrate this memorable improvement, and the hard work of so many people that made it possible, without losing sight of the much more work clearly to be done.”

One area that improved over the past three years is the representation of disabled people in synagogue clergy or staff. While 22 percent of local people surveyed said that they knew disabled clergy or staff at faith-based institutions — an increase to the 2018 response of 18 percent — the majority responded that they didn’t know anyone.

“We need more targeted leadership training programs for people with disabilities. When we don’t have models, we don’t know it’s possible,” Tuchman said.

She added that many disabled Jews lack financial resources to study for the rabbinate.

“There are a lot of folks out there that do provide scholarships and need-based assistance for rabbinical students, but there isn’t a lot out there that is directly targeted or directly aimed at people with disabilities,” she said.

Respondents both nationally and in the Washington area cited prejudice and “unacknowledged stigma,” as the biggest barrier to fully include people with disabilities. Unacknowledged stigma refers to the lack of open discussion about disabilities and disabled people, which alienates the disabled and abled from each other.

Tuchman said that this unspoken “othering” often leaves many Jewish disabled people to feel like strangers in their community.

“Whether people realize it or not, people with disabilities aren’t thought of as peers. We’re thought of as people who we bring in from the outside as a nice thing to do, but not as integral members of the community,” she said.

Arielle Silverman, who serves on The Jewish Federation of Greater Washington’s disability and inclusion committee, said that stigma isn’t always outright exclusion. Sometimes it’s what abled people do to be “nice.”

Silverman, who is blind, said people will sometimes come up to her and, without asking, steer her body in the direction they think she wants to go.

“They wouldn’t do that to someone without a disability,” she said. ”So they see the disability as a reason to behave differently toward a person. And they don’t think it’s a prejudice because they’re being nice.”

Aaron Kaufman, senior manager of legislative affairs at the Jewish Federations of North America, said he wishes people didn’t try to deduce how his cerebral palsy affects him. This leads to people talking down to him.

“People automatically assume there’s some cognitive impairment. But, even people with intellectual disabilities don’t like to be talked down to,” he said.

In addition to inaccurate perceptions, Kaufman said that at times he senses that people sometimes include him out of obligation, not because they want to.

“I’d like it to get to a point where they do enthusiastically. As a person with a disability, I can always tell when someone is including me begrudgingly or because they really want me,” he said.

Lizabeth Katz, vice president of the Washington Society of the Deaf, said that for deaf and hard of hearing people there is a lack of financial assistance by Jewish institutions to help them afford interpreters to participate in community events.

“It’s going to take more than a one-time grant to solve the problem,” she said.

Katz would also like to see more people make an effort to interact with disabled people in Jewish spaces, especially with deaf and hard of hearing members.

“Inclusion also means access to building relationships in the community. It is the relationships that brings people back,” she said.

Including disabled people isn’t optional, according to Tuchman. Not doing so would mean isolating a portion of the Jewish community.

“We are a part of the community,” she said. “The accommodations to make a more inclusive community are simply letting members of the community access the community.”